https://frompoverty.oxfam.org.uk/are-we-allowed-to-be-unimpressed-by-nobel-prize-winners-hope-so/

就是啰

有确凿文字考古记载的中国历史就是从公元前1000年左右的商朝开始的,也就3000多年吧

什么5000年历史。商朝之前的,都是中国人的神话故事,自说自话。

继续启蒙

中国人对如何判定历史文明的起源有常识性错误

定义文明的起源,远不是挖出几个破锅,破瓢就算文明起源了

还要有确凿的考古文字记载,能够反映那时具有城市中心,文化和治理的复杂社会,才算是文明的起源

中国能够追溯最早就是3000多年的商朝

中国人说的5000年是典型的打嘴炮

对对对,您就是一神话

对对对,您就是一文明起源

您的标准是唯一的

真善美

真善美

大师

然后一步一步走向欧洲病夫?

你是瞎了吗?英国已完你欲绝承认要堂吉柯德吗?

美国靠暴力屠杀土著和内战建的国,现在多优秀?

诺贝尔奖有颁给过书吗

3000年还是5000年,重要吗

就知道抠字眼,你是真的读过书吗

你就别掺乎了,一下把调调打low了….

一步步走向“病肤”的是中国自古以来几千年的几乎每个王朝循环的最后环节,不断重复这个“死循环”。你看英国现在的“朝廷”technically 还是当年君主立宪后和平过来的朝代,这么久是不是已经超过中国各王朝的“寿命”了?

美国那点屠杀和中国多个重大王朝所搞得屠杀人数比,就是小儿科,绝大多数印第安人其实死于欧亚大陆带来的传染病,美洲人没抗体。何况美国现代早都认错了,Native American 能不交税就是补偿之一。

technically英国每次换党就是改朝换代

都还没有ccp连庄久,更别说我们那些几百年的朝代了

美国你没有get到我的点 我说的是暴力建国也能很强,并不要像英国一样磨磨叽叽主动弃权,

那是换看家的,和转移矛盾的靶子

大哥,高低谁人在乎

不过是给那谁以the British public 自居,再教育the Chinese 的满足感

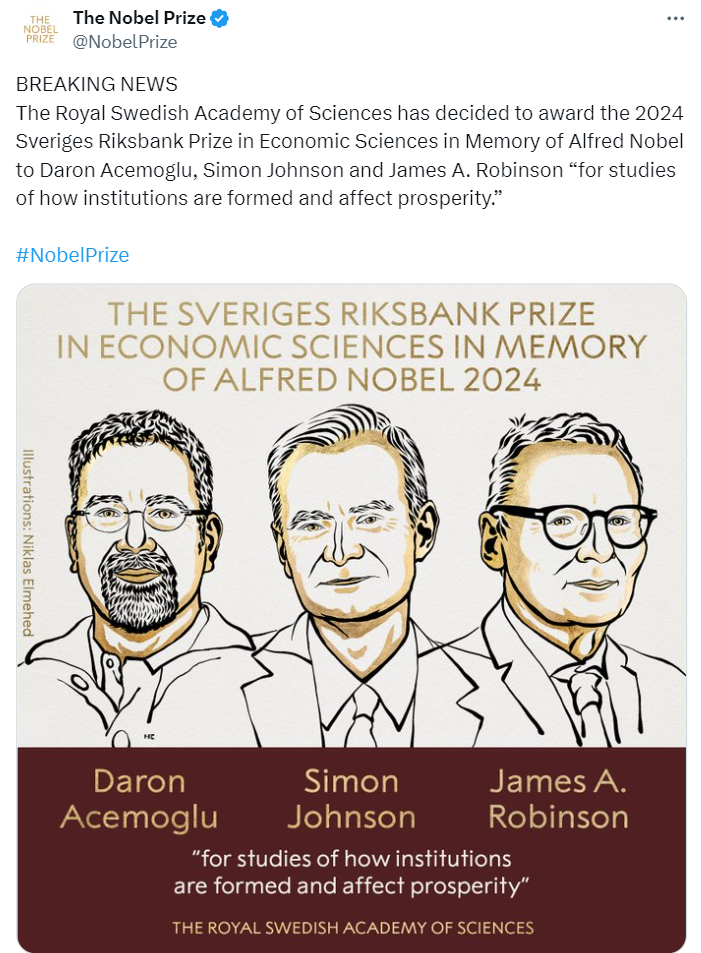

Are we allowed to be unimpressed by Nobel prize winners? Hope so.

October 14, 2024

By Duncan Green

When I heard that the not-quite-Nobel for economics this year had gone to Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson and Simon Johnson I went back to my 2012 review of their breakthrough book, Why Nations Fail. At the time, I had really mixed feelings about it – loved the emphasis on conclusions, but detected an extraordinary level of Western bias on which institutions they thought were effective. Above all, like many Western political scientists, they really struggled with the sustained rise of China. I concluded ‘Overall, the book left me with a sensation of raised expectations, sorely disappointed.’ Francis Fukuyama was similarly critical at the time. The intervening 12 years have, if anything, confirmed my concerns.

Here’s the review:

‘Every now and then, a ‘Big Book on Development’ comes along that triggers a storm of arguments in my head (it’s a rather disturbing experience). One such is Why Nations Fail, by Daron Acemoglu(MIT) and James Robinson(Harvard). Judging by the proliferation of reviews and debates the book has provoked, my experience is widely shared).

First, what does the book say?

‘The focus of our book is on explaining world inequality’, which is essentially a phenomenon of the last 200 years (certainly at its current extreme levels) – the average income of a conquistador was only about twice that of a citizen of the Inca empire.

Inclusive Institutions rock: ‘Countries like Great Britain and the US became rich because their citizens overthrew the elites who controlled power and created a society where political rights were much more broadly distributed, where the government was accountable and responsive to citizens, and where the great mass of people could take advantage of economic opportunities.’

Politics trumps economics: ‘While economic institutions are critical for determining whether a country is poor or prosperous, it is politics and political institutions that determine what economic institutions a country has.’

Failure is the norm: ‘To understand world inequality we have to understand why some societies are organized in very inefficient and socially undesirable ways. Nations sometimes do manage to adopt efficient institutions and achieve prosperity, but alas, these are the rare cases. Most economists have focused on ‘getting it right’, while what is really needed is an explanation for why poor nations ‘get it wrong.’

One of the core problems of most institutional arrangements is that those in power have ‘a fear of creative destruction’ – that the disruptive effect of innovation and capitalism will undermine their power base. The luddites in the presidential palace or the chamber of commerce do far more damage than the protesters on the streets. They therefore act to stifle it – elites’ interests are opposed to those of the long-term development of their country. An ‘iron law of oligarchy’ means that even when oligarchs are overthrown, the revolutionaries, like the pigs in Animal Farm, often come to resemble them. ‘New leaders overthrowing old ones with promises of radical change bring nothing but more of the same’. Understanding how change doesn’thappen is as important as understanding why it does.

In contrast, when a combination of institutional accident and leadership leads to an elite that has reasons to accept creative destruction (as, the authors argue, is the case in the US), then a take off can occur, requiring a rare combination of political centralization and the tolerance of disruption.

The style is captivating – dotted with great historical accounts, amusing and telling anecdotes (in the 16th Century African kingdom of the Kongo ‘taxes were arbitrary: one tax was even collected every time the king’s beret fell off’). Great use of contrasts and ‘natural experiments’ – Mexico v US at the border; Bill Gates v Carlos Slim; North Korea v South. The pace is breakneck, hopping manically between countries and centuries, from the rise and fall of the Roman Empire to the disappearance of the Mayas to the rise of Japan, plucking examples to illustrate the thesis.

The strongest part of the book for me was its focus on the dynamics of change. It almost feels like physics – path dependence is key; minor ‘butterfly’s wing’ differences in initial conditions caused by gentle ‘institutional drift’ make a huge difference when a country hits a ‘critical juncture’ (e.g. the French Revolution, or the Black Death in 14th Century Europe, which wiped out a large part of the labour force and so transformed economies), and can set them on diametrically different paths. ‘The richly divergent patterns of economic development around the world hinge on the interplay of critical junctures and institutional drift. Existing political and economic institutions – sometimes shaped by a long process of institutional drift, and sometimes resulting from divergent responses to prior critical junctures, create the anvil upon which future change will be forged.’

The problem is, much of this only really works in hindsight – almost by definition, there are always lots of minor differences floating around, and it’s impossible to tell in advance which are going to provide the butterfly’s wing that determines that (for example) the industrial revolution takes place in Britain and not Spain.

However, there is more substance than that – revolutions based on broad coalitions (e.g. Britain’s 17thCentury ‘Glorious Revolution’) tend to lead to demands for more inclusive political institutions and are less likely to degenerate into copies of the very autocracy they have overthrown.

The trouble with these grand theories is that when they coincide with your own prejudices, they feel like a flawless romp through history. But if you are uncomfortable with the numerous assumptions, explicit and implicit, you get a sense of suspicion and vertigo – it feels like you’re being conned (and the complete absence of footnotes make it harder to check the source of some of the sweeping claims). The reader is being asked to take an awful lot on trust here. And I kept hearing a phrase of Thandika Mkandawire’s in my head: ‘a theory that explains everything, explains nothing.’

The book’s biggest problem is the authors’ love affair with the American Dream (though not American Reality). In their account, successful institutions bear a remarkable resemblance to America’s constitution, separation of powers etc etc. That means that the China question hovers over the book throughout, and their fairly perfunctory attempt to answer it is deeply unconvincing. China is portrayed as on the wrong side of history, pursuing ‘authoritarian growth’, while trying to defy an inexorable push towards matching economic inclusion with the political equivalent.

But can this book really be arguing that China’s economic transformation is substantially more fragile than that of, say, Brazil? Apparently so. ‘Growth under extractive political institutions, as in China, will not bring sustained growth and is likely to run out of steam’ is a hell of a throwaway line, especially when you don’t say whether that might be in one year or a hundred. Nor do they buy into the optimistic liberal account that holds that China’s growth will create pressure for political reform – A &R think it will hit a growth ceiling before that reform happens, with unforeseeable, but chaotic consequences.

More generally on the role of the state, the book seems to swallow the rather discredited argument of the ‘East Asian Miracle’ school that ‘South Korea is a market economy, built on private property.’ (Dani Rodrik and Ha-Joon Chang beg to differ.) The authors systematically downplay the role of industrial policy and a hands-on state in its take-off . ‘[The] process of innovation is made possible by economic institutions that encourage private property, uphold contracts, create a level playing field and encourage and allow the entry of new businesses…. It should therefore be no surprise that it was South Korea, not North Korea, that today produces technologically innovative companies such as Samsung and Hyundai.’. There is no real attempt to explore the concept of ‘developmental states’, a term originally coined to describe Japan’s take-off, but one which is increasingly interesting a range of developing countries as they see the more liberal capitalist economies being rapidly overtaken by ‘state capitalists’ like China and Brazil. But for A & R, the high growth figures of countries like South Korea are always ‘in spite of’ a hands-on state, not ‘because of’.

Which all reminds me of a baffling exchange in 2003 with the FT’s Guy de Jonquieres, as we looked out over the beach at the WTO summit in Cancun (NGO advocacy is a tough gig sometimes). Me: ‘how can you say state intervention destroys economies, when South Korean industrial policy has been so successful’. Guy: ‘But think how much better South Korea would have done if the state had stayed out of it.’ Err, right.

Overall, the book left me with a sensation of raised expectations, sorely disappointed. That was summed up in the book’s bizarre finale. After a hyperactive romp across the millennia this purported survey of what works ends up pinning its hopes on – wait for it – the media, Facebook and Twitter. Oh dear. All that history ends not with a bang but a tweet.’

October 14, 2024

/

Duncan Green

哈哈哈

就是啊

可惜他们看不懂听不到

只会看叛逆自媒体的小短片儿

小短片儿列表如下

伊朗报复以色列行动开始,以色列做好准备,接下来中东会混战么?

美国最近终于搞出靠谱的超音速导弹了,这能让战争可能性进一步降低吗?

应网友lzb2811的邀请,大家来聊聊台湾海警在金门撞死大陆渔民的事,此事的一些疑团我不太了解,请教谁知道到底怎么回事

看似最近UCL“惹事”了,教授被中国留学生举报“歧视”,这个事大家怎么看?

请教一下,大家觉得最近国内“义和团”围攻农夫山泉是怎么回事?

大家来评论一下,这个BA飞机上的incident 是“辱华”,“歧视”,“玻璃心”,“粉红” 还是别的?看完觉得挺搞笑

竟然还有人做了境外模拟GFW发GitHub,可以在家搭墙,需要的时候自己再翻出去 LoL

这个请教懂得朋友来评一下,中国防空导弹真的防不住伊朗的导弹空袭?

为什么我们华人要远离radical“粉红”思想 - 这个案例中的“粉红”被判刑

钢琴家Dr. K和”粉红”大战St. Pancras 故事后续 - 客观观察